XVII – When Brandon Hoped Rachel Woke Up (and Randy Didn’t Have to Go Fishing)

Work entered Jesse’s mind for the first time in a few hours. If he’d been able to see any of the emails his manager had sent Friday about Jesse’s “recent episode” and the reasons that he’d listed justifying his “overdue termination,” every nerve in his self-righteous body would have lit up in defense of himself. And if he had seen that Steve over in asset management had taken his chair (everyone knew Jesse may not even get to come back after his bereavement) he would have felt fire in his cheeks and chest. But since all he saw was hot air rippling off the Cracker Barrel parking lot’s blacktop and Pastor Matt’s white Honda CR-V, his resting heart rate was about a hundred and his head was still undistracted enough to figure out how inconsistent his philosophy was.

Something he couldn’t put words to seemed to be screaming that the indignance he felt about his father’s refusal to come out of the place he’d locked up inside his own mind, the affection he’d witnessed in Randy and Matt (and Joe), and his life’s long work of constructing a neon sign over the world that flashed “meaningless” didn’t add up. How could he be indignant about one thing and find another one commendable if the word was really meaningless?

“I don’t know,” he said out loud and stuck his chin out a bit as he considered it for the first time. Since Pastor Matt had just said something like, “What do you all have planned for the rest of the day?” no one thought he was crazy.

As they got into Matt’s CR-V and he turned the A/C to full blast, Joe, from the passenger’s seat, turned his head just slightly back and said, “I’d like y’all to sleep at my house tonight. It’ll save you some money on a hotel.”

Even in his agitated state, Jesse found something charming about the way Joe put the accent on the first syllable. And he smiled, and nodded. Randy, to his right in the backseat, grinned with all his insanely white teeth.

“Thanks, Joe,” Jesse said.

“Joe, I’m gonna’ go visit Mary and help her with grounding some electric in her house.” Pastor Matt had spent three years as an electrician before going to seminary.

Joe grunted, gave a knowing nod, looking straight ahead. “If you boys would like to join me, I’m going to go fishing down at Hammertown Lake.”

Randy grimaced under those cheap, God-forsaken Blues Brothers sunglasses that for some reason were worming their way into Jesse’s heart and growing on him. Randy had only gone fishing twice, and both times he’d dry heaved when he’d touched the fish his friend had caught. It had been so slimy and oily and the fact that it squirmed when you held it, as though it were looking for a way into your body where it could keep swimming and stay alive, gave him night terrors. Matt looked at Randy in the rearview mirror and smiled.

“I’ll come,” Jesse said. There was something in it, something he couldn’t name. But it had to do with the picture of him and Joe out there in the hot afternoon sunlight next to the water.

“Any chance you’d want company, Pastor?” Randy asked Matt. “Sure,” he said, smiling as he stopped at a red light and turned the A/C down a notch.

Jesse reached into his left pocket and felt the sheet from his dad’s old composition notebook that Jesse had given him, the one he’d been reading out on the Cracker Barrel front porch. The one that made no sense.

We both know what the old man’s like, Huck. Know what he can’t do. Know what he is. And you’re going to leave him here with me?

You’re guilty as sin, boy. Guilty and that’s why you run. We’re both guilty, Huck. But I stayed.

I decided what to do with you. It was last night. I was down there and I had this thought about how we’re really not the same. I wish we were, I wish you had the same parts as me. But I know now you never did. Not even that filthy hair, brother. So I sat on my chair down there and I knew it was over.

You’ll never understand, and I know now you never tried.

Yeah, I decided, and so there’s an axe down there now.

See you soon, Huck.

Brandon threw up in the hallway. A nurse called someone to clean it up, and he looked at her after she hung up the phone at the nurses’ station, but he barely noticed her.

Rachel’s mom and dad were on their way. He hadn’t called his parents yet. One tooth was chipped, another gone. Her nose was probably broken. She was in the room, now, and he was out in this hallway trying to understand what had happened and what would happen.

Where had she been going?

She wouldn’t wake up at first when they brought her to Emergency on a stretcher. He’d been walking quickly with the two guys pushing the thing, staring at her bloody and swollen face and wondering how he could handle it if she died, terrified about what would happen to her and what they’d do to her in the room once they got there, feeling white heat in his nerves and behind his eyes as he wondered what kind of pain she was feeling.

“What are they going to do once we’re in there?” he’d asked them. His voice had been loud, as always, but it was frantic, too. Brandon was almost never frantic. Brandon made everyone laugh. He put everyone at ease. If you were over forty he was your crazy kid brother and if you were under twenty he was your crazy uncle, wearing his Space Ghost or Fantastic Four t-shirts and smoking that pipe he kept in the center console of his car and clogging toilets so badly that the church had to cancel a Wednesday night service. But Rachel’s nose had been swollen to the size of her fist and her mouth had been covered in blood that hadn’t fully dried yet and her eyes had been closed. Still. Asleep. He had never seen someone sleeping through that kind of pain. He’d unraveled.

“They’ll check her vitals first, and then they’ll examine her and treat her facial injuries.”

Brandon hadn’t truly run since he was a teenager, so he’d had trouble keeping up with the guy on the right, the one he’d asked. Maybe that was why he threw up after they were gone and Rachel was in the room. Now he wiped his mouth with his t-shirt collar and went in there where the nurse was just taking the blood pressure cuff off Rachel’s arm.

“And she was being treated for a miscarriage?” the nurse asked him as soon as he was in the room. She was middle aged and had brown hair pulled back into a ponytail and something about her registered with Brandon in a good way and he instinctively trusted her.

“Yes,” he said, his voice sounding angrier than he felt, deep and loud but trembling a little as he wondered how scared she’d be when she woke up. “What happened?” he asked, sounding angrier still.

“I’m not seeing anything indicating a seizure, so the doctor will be in shortly, but I’m going to guess that she fainted from stress and exhaustion. How long ago did she leave her room upstairs?”

Brandon blanked. He had trouble remembering what the room looked like, what floor it was on, what the name of this hospital was. “Um, I guess it was about ten minutes ago.”

The nurse looked up at him, something in her eyes seeming hostile or perplexed, but Brandon missed it because he was looking at Rachel. He wanted to rip something apart. He wanted to destroy something. A constellation of things about her lit up his mind as he looked at that blood on her face. How small her hands were, the pink sneakers she’d worn when they walked around that outdoor shopping plaza the day after they’d found out she was pregnant, the way she squinted when she was pretending to be angry. And looking back bred love almost as quickly as looking ahead bred fear, so now he wanted to hold her hand and wipe away that blood and kiss her forehead.

How could he get her back there? Back to that baby store at The Commons downtown where her eyes were bright and he was mostly listening even if he was a little thinking about his D&D event that weekend and then decided to buy her frozen yogurt with his last six bucks until payday because she was just too happy for him not to try to make her happier? How could he help her heal from this and how could he give her another baby?

And then he thought about his son, their son, and his heart was all grief now. Love and grief, things both nourished by the past. It was the future that fed fear.

“We’re going to stay here and see what she’s able to tell us when she wakes up.”

“Yeah,” Brandon said. He put both hands on his head, interwined his fingers, and closed his eyes.

When.

It’s not that Jesse had never been fishing. It’s that he’d never even actually seen a fishing pole in real life.

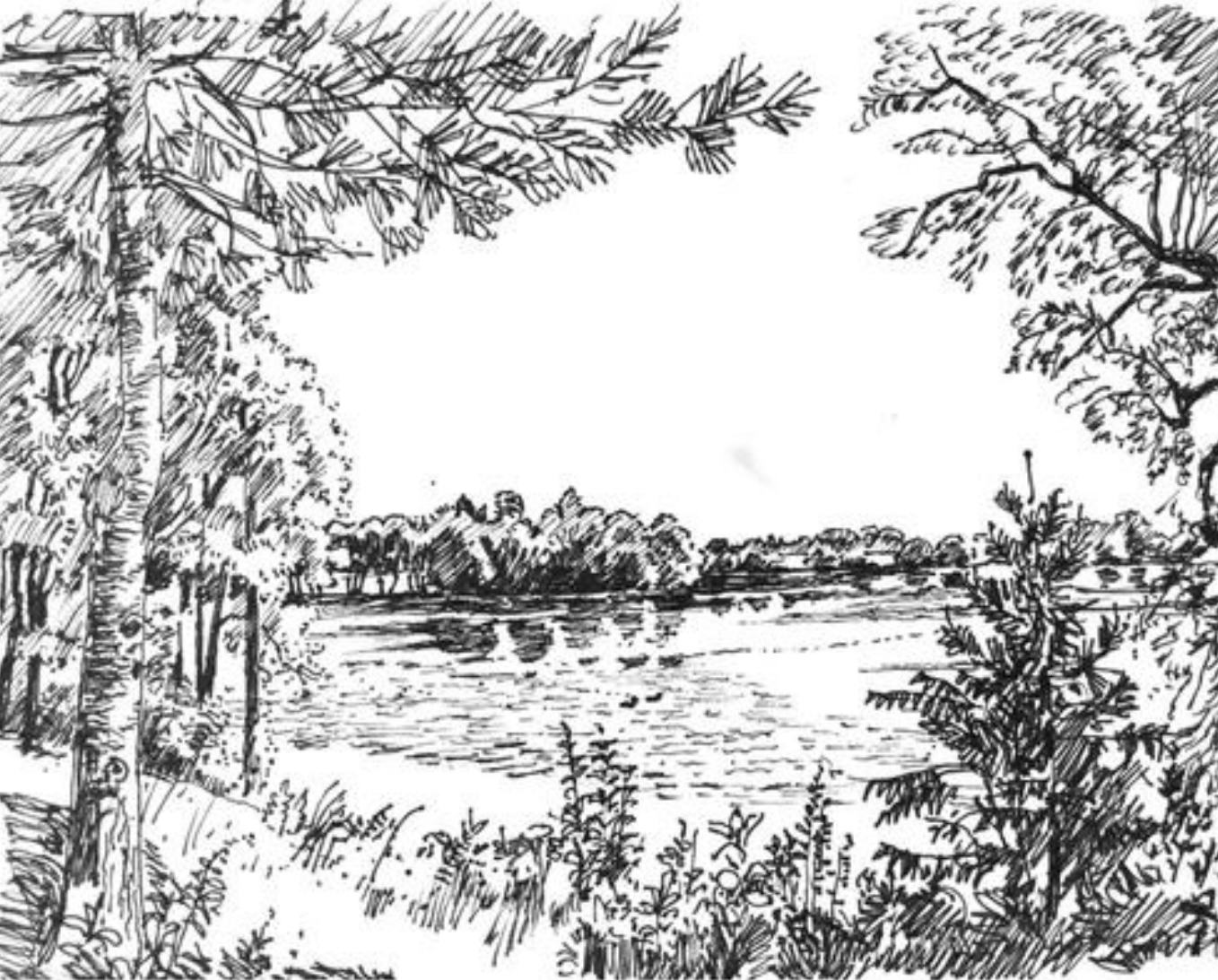

He didn’t have any idea what was actually involved in catching an actual fish. So he watched Joe use his massive hands to place the tiny nightcrawler on the hook as though it were Cirque de Soleil. And then when he saw this fairly squat, slow old man cast his line with speed and tenderness, he felt like he’d just seen magic. He had a thought for a second that he could now imagine Joe kissing his wife. But the thought felt too private to indulge, and he had the sense that Joe could read his mind, so he shook his head and sat down on the dirt a few feet away from him.

“My wife hated it here,” he said. Jesse scooted further away, wondering whether it was more likely that he was dreaming or that Joe really did have super powers, but before he could decide, Joe went on. “She liked fishing, she just hated it here. The long walk from the parking lot, mostly. She told me I was silly to come here when I’d only ever caught two fish at this lake. Both the first time, too.”

He held the pole in one hand, gazing out at the green-brown surface of the water. Jesse realized Joe had worn a t-shirt to church. A plain white t-shirt, in good shape but still a t-shirt. It surprised him.

“How long have you been going to that church?”

“Since I was a boy,” Joe said, trailing off at the last word as though he was giving it up begrudgingly. Which he wasn’t; Joe never gave away anything begrudgingly, not a word nor his tithe nor the eight-year-old Jeep Grand Cherokee he’d given to Alex Johnson before he left for Bible college last summer. But he’d thought he had a bite right when Jesse’d started speaking, and he realized now it was either false hope or the little critter had gotten away. It was all false bites out here, he supposed.

“Did you and your wife meet there?”

“Yep,” he said, knowing that wasn’t all Jesse wanted. What Jesse wanted was something Joe wouldn’t be able to give him. Even though, truth be told, he wanted to. He’d thought about young Bruce Henderson most of last night, and he’d thought about him right before saying his prayers that morning. But he’d told Jesse everything he knew, or at least everything he remembered. “How’s your boy? If you don’t mind my asking, that is.”

Jesse did mind his asking, but Joe had too much weight with him to give anything but the truth. “I don’t know.” He picked up a stick at his feet and suddenly felt very silly sitting in the dirt in a suit out at a lake next to a three-hundred-and-fifty pound slob who was imitating a Bob Ross painting, even if the slob was about the wisest person he’d ever met. This whole thing kept getting weirder and weirder. “I don’t know what I’m doing out here, Joe.”

Jesse expected him to say, “Fishing,” but instead he said, “You’re trying to find your father.” And then he reeled back in the line, slowly, the clicking making a very pleasant sound out there in the quiet of the lake shore, where it was currently just the two of them. “And I hope you do. What you need to know, though, is that won’t change what’s happening with you. You’re scared, Jesse. And I don’t reckon anybody was ever really scared of something that already happened. People get scared of what’s coming.” He looked over at Jesse and raised his thick eyebrows, and looked into him the way he looked into the new young mail man the other day when he’d handed him his Cabella’s catalog and almost made him soil himself. Joe’s face always cut through you. He thought so little about how he came across and so much about what he was looking for that sometimes his mouth never changed shape during a whole conversation. It was like being interviewed by a bust of Plato.

Is this really what fishing was? He had to be missing something. Joe was just standing there in this heat looking at water. It was like a tease. And he never caught anything? Was this some sort of Christian exercise, like Buddhist meditation or something?

Joe was right. He was right. He was always right, which was infuriating and comforting.

“Yeah,” Jesse said, and turned his head back to the water.

Tall green trees all around the lake, the sun just beggining to drift down behind them. When was the last time he’d been out in a forest like this? Ten years? Twenty?

“What do you think I should do, Joe?”

He hadn’t asked Randy. He hadn’t asked Janie. But he would never see Joe Granger of Jackson, Ohio again, and he respected this retired old guy with a heart like old, stained maple wood in an old heirloom cabinet that would stay with a family for generations. Joe told him the truth, and he cared what happened to him, and Jesse could lean on what he said good and hard. That’s no small thing for a tired man, having a friend whose words you can rest on for a bit like a cane. Plus it was hot out here and he would cut off his left hand for a Fresca, so delirium was setting in.

Joe kept looking out at the line, knowing it wouldn’t move, because nobody fishes in the middle of a summer afternoon, though Jesse didn’t know that. Pastor Matt had known, but he was wise enough to know what Joe’s intentions were and keep his mouth shut. This boy was at least two kinds of scared, and this late in his life Joe would’ve struck a deal to forego his remaining years and head on home in exchange for some peace for the grown son of a tortured boy he’d been unable to save a lifetime ago. But the real God doesn’t strike deals like that, and Joe Granger knew Him just well enough to know as much, so he stared at his fishing line, which might as well have been sitting in the grass behind them for all the good it was going to do, and he said what he’d wished he’d said back when he was a young man and Gladys was a young woman and the babies looked like they might come someday, back before they didn’t.

“My Jesus is here, Jesse. He’s up in Heaven, but He’s here, too. Just something He can do since He’s the Lord. And it’s not luck that brought you here to town and gave us time to talk. He comes after people like that. It’s just who He is.”

Jesse heard a woodpecker somewhere out there now, and he noticed the sound of the cicadas for the first time. And this place was so beautiful, and he wanted Joe to be right so badly, but right at the backdoor of his mind that fear was scratching. No job, Janie gone, Jeremiah halfway to gone, and a father who was something bad he’d hidden. And something else. He was scared of something else, too.

He swallowed and diverted his attention to the sound of the woodpecker as best he could, and studied Joe’s old, thick hands around that red fishing pole. Man, that thing was old. How often do people buy fishing poles?

“You think you’re doing the chasing, Jesse. You’re not.”

And Joe looked over at him, and he found what he wanted, forty feet deep into Jesse’s eyes. He turned back to the water, still as the surface of a pool table.

“Nothing biting today.”

Jesse felt the scratching get louder.

“There’s still time.”

Joe reeled in the line a bit, turning the handle for the first time in twelve years, the first time since a year before Gladys had died.

Because Joe Granger didn’t fish anymore.