XII – When Jesse’s Holiday Inn Used to Be Gladys’ Church (Because Things Change)

A Story for Anxious Times

Chapter 12

For the previous installment of this serial novel, visit here.

True, there were lots of things that were different in 1966, but teenage boys still liked cars. And Joe Granger had a nice car.

Which is what this odd and silent sixteen-year-old new kid named Bruce had first been drawn to. Joe Granger’s 1965 Pontiac Grand Prix. He’d stared at it from his aunt’s front porch one Saturday, barely blinking as he took in the shape and thought about what would be firing and moving when you pushed the accelerator to the floor. He thought about what it would have been like to craft each piece and attach them and then drive it fast and far as it rumbled underneath and around you and it carried you, or you carried it, eighty miles an hour down a highway that was fresh and new.

Joe had invited him over with a simple hand wave, but at that Bruce had turned quietly and gone inside. Then two days later, while Joe had been at work, his wife had waved gently at Bruce, and said hello, and asked if he had a driver’s license, because she needed to get to the drug store and had just broken her glasses the other day.

He was the strangest young man Gladys had ever seen. He was painfully quiet. Every time he looked you in the eyes he then immediately looked down at the ground, as though he were ashamed at your having to see him. He didn’t smile, didn’t frown, didn’t really move his mouth at all. But Gladys felt for him, and she had the slightest extra coat of courage and the quiet inability to shake a particular thought bound to that courage that she associated with the Holy Spirit’s calling her to do something. So here she was in the passenger’s seat of her husband’s car as Mrs. Lowell’s mysterious nephew, with no driver’s license to speak of but a quiet assurance that he could indeed drive (as good as the actual license in Jackson, Ohio in 1966) took her to the drug store.

He was a good driver. It was only a mile and a half to the drug store, and he was driving about twenty miles an hour and clearly watching the road.

“Do you like living with Mrs. Lowell so far?”

The young man squinted his dark eyes just a little and looked to the left for a second, then quietly said, “Yes.”

What was it about this boy? Despite his childlike silence and fear of her, he was almost a grown man, obvious from his muscular build. And yet she wasn’t scared of him. The bare facts, taken by themselves, would be reason for a woman to be nervous about letting him drive her somewhere, even if only a five minute drive to a drug store in the center of town. Here was an almost grown young man, unapproachably silent, arriving unannounced to live with his aunt. Even with his new cleanly cut flat top, he still didn’t resemble the typical well-raised teenager. His shirt had several holes and a tear at the collar, his slacks had grease stains around the pockets. And the way he narrowed his eyes and looked away from people gave the obvious impression he was trying to hide. So why was she not nervous? And why was she so unable to stop praying for him, right here in the car?

Have you ever come across an injured bird? Gladys had once, a robin who had been dropped by a cat in their front yard. One eye had been gone, and it couldn’t move much, though when she’d gently nudged it with the corner of her shoe it had stretched its wings and opened its mouth wide, slowly and silently. She had wanted so badly to help it, to restore it, to give it something good. But when she’d come back out from checking the casserole she had in the oven, it was gone. Probably picked back up by the cat. This young man, the exhaustion on his face, the despair and guilt in his eyes, she couldn’t quiet the fire in her heart to love him, to tell him about who Jesus was and what He could do.

He pulled into the parking lot of the drug store and turned the car off, pulled the key out of the ignition, and handed it to her without looking up at her.

“Would you like to come in with me?” And when he looked down and closed his eyes was when her heart stopped. Because at the bottom of his neck, at the back just above his shirt collar, she saw an open sore that looked infected and very painful, and she knew at once that this boy had something to hide. Some piece of what he was and what had called her fell into place, and without any conscious effort she said, “Come in with me, please. I could use some help carrying the things.” And without ever looking up he opened his door and stepped out into the morning sunlight.

Three Sundays later, teenage Bruce Henderson was in the backseat of Joe Granger’s car as he and Gladys took him to service at First Baptist. The open sore, two inches long, on the back of his neck right above his right shoulder had fully healed by now. Gladys had bought some hydrogen peroxide and sent him home with it. She had told Joe everything and yet still she felt like some piece had been left out. What she couldn’t convey to her husband was the weight in her chest and her head when she looked at this boy, the pain of a mother who’s never had a child but has found the one she’d love to have had. The hands and the hair and the eyes and the whispered voice she wants to keep safe and guide home. But then Joe didn’t need it conveyed. He understood some of it, if not all, and that was enough for her now. That’s why he had been the one to invite Bruce to church each of the last three weekends, and she loved her husband deeply for it.

They sat in their regular spot in their regular pew, but of course everyone wondered who this boy was who was sitting with the lovely young Granger couple who had no children. But the confused or interested looks in the dim brown sanctuary weren’t her concern. She loved this church and people, and she could forgive their not understanding this effort of strange love, just as they forgave her own failings. What was on her mind, during each hymn and both prayers and the entire sermon, was this boy and his sins and whether his heart could be found by the Lord who could repair him.

John 6:26-40 was their pastor’s text.

Please, Father. I don’t know what evil things boy has done or has been, but this has been your doing, I am sure of that much. The wood on the floors creaked as the restless children in the next pew squirmed, and Mrs. Crinch next to the boy had so much perfume on, but oh please, Father, save this boy.

“For I have come down from Heaven, not to do my own will, but the will of Him who sent me. This is the will of Him who sent me, that of all that He has given me I lose nothing, but raise it up on the last day.”

Ancient words. In this sanctuary smelling of old cigarette smoke and aftershave and Mrs. Crinch’s perfume, this simple place of all the depth and breadth of 121 hearts pointed towards true north but stumbling in different ways, and at least one spinning idly on the compass face from fear and guilt and hate, these words would outlast every good and worthwhile thing. They were the old words, the true words, and that sore was gone, and his head was further down than it had been in the car, and his eyes were closed, and oh God please save this boy.

“For this is the will of my Father, that everyone who beholds the Son and believes in Him will have eternal life, and I myself will raise Him up on the last day.”

And Gladys prayed. And she had no idea that sixteen-year-old Bruce Henderson was terrified of what would be raised up on that last day.

“So what is it?” Randy asked as they walked back to the pickup truck.

“A trail.” Jesse opened up the passenger’s side door and sat down, setting the styrofoam box with the sandwich in it in between him and Randy and squinting as he looked through the windshield at the dark gray sky.

“To what?” Randy asked, starting the truck and looking behind him as he pulled out and prepared to head to the Holiday Inn where they’d agreed to stay.

“I’m not sure exactly. But I think he left these things for someone who’d know what they meant. If they found them. I’m not sure what the two routes are, but I’m sure that this is a trail between his house, his home, and here.”

Jesse closed his eyes as Randy turned on the windshield wipers. The rain had started up again, and the rhythm of its pelting the bed of the truck and the blades against Randy’s windshield helped him think.

Why? Sixteen years old, running from some thing he’d done or seen, something he’d never talk about again, leaving family forever.

Why leave a trail?

What was Janie doing now?

The thought was like a hot bullet to his chest, dead center. His marriage was over. And even aside from money and a fight over Jeremiah, he wanted to cry about that fact. What had happened? How did you love a woman enough to marry her, to pledge your future to her, and then hate her and have her hate you back? How did that erosion happen? How does this thing that feels like the truest thing you’ll ever know turn into something dreary and painful and bitter?

She was probably watching Jeopardy with Jeremiah. Jeremiah loved the way the questions showed up on the screen, some combination of the font and the sound that the Daily Double made was soothing to him. They were probably on the couch Bruce had been on with Jeremiah that last day they’d seen each other. Janie would be stroking his hair, but she would still be seething that Jesse had left them right now. She knew something had happened the night Bruce had died, but no idea what. Jesse wouldn’t tell her.

Why should he? It wasn’t her father. And he was so tired. And when the words started to flash in his mind, the three or four times he started to tell her, they caught in his chest, and he couldn’t even open his lips. He just saw a woman he neither trusted nor loved, though he wanted to do both, and he held back what was his only hope.

Somehow his father had known Jesse needed to know this now. So maybe he did. And maybe it would change something.

Randy pulled into the Holiday Inn.

“Here we are, Champ.”

“Champ?”

“Yeah, just trying it out. No good?”

Jesse shook his head, picked up the box from the diner, and stepped out into the rain. He pulled his suitcase out off of the floor where they’d stashed it earlier, when the rain had started. Randy carried his t-shirt bag.

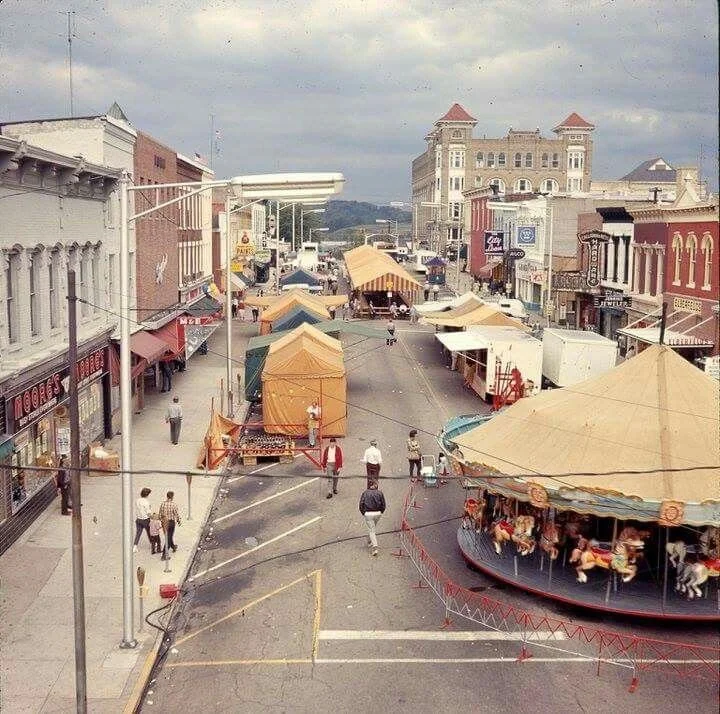

“I changed it to two rooms,” Jesse said, staring straight ahead at the big sliding doors and wondering what had stood here forty-five years ago. “They’re side-by-side. I got it.”

“You didn’t have to do that, man,” Randy said. But Jesse waved it off without looking at him, not wanting to devote the mental energy to rolling out the standard issue niceties.

How did this end? When he went back, he still had no job and a dead shell of a marriage. So what could this really change?

The two of them stepped into the nicely decorated lobby and saw the front desk to their left. Jesse walked up and gave the fortysomething lady his phone number, confirmation number, and credit card.

When they were done checking in and Randy put his room key in his pocket, he finally noticed he had a voice mail from Brandon.

“Oh, shoot; I should call this guy back. You mind? You want to meet back here in a few, have a cup of coffee or something?”

Jesse nodded and then turned to head to the elevator. And something about his reflection in the mirror at the end of the hallway sprung on him the idea to call Janie. He flipped open his cell phone, still (thankfully) working since it had dried out Wednesday night, and dialed her cell phone number.

A second into the third ring he heard, “Hey.” Immediately he got angry, indignant at how melancholy she sounded while he was drowning. She chose to have no sympathy. That’s what he assumed, and why he decided to give it back.

“Hey.”

Three seconds of painful silence later, Jesse asked in an irritated tone that he didn’t notice in himself, “So how’s Jeremiah?”

“He’s okay, I guess. We just finished Jeopardy.”

Jesse smiled since the simple joy of imagining his son’s giggle at the Daily Double sound was too quick for his best efforts to be indignant and cold towards to Janie to suppress. And he was even about to say that that was good and ask Janie how she was. But he reigned it in just before the first word fell out of his mouth. And so instead there were another few seconds of silence, a few seconds that were packed with land mines neither of them wanted to trip themselves, but on which they each would have loved to see the other step. Janie gave a nudge.

“When are you coming home, Jesse?”

They both knew that the subtle barbs in that question were exquisitely placed. Janie could easily hide behind plausible deniability, claiming that it was just a simple question. And yet putting his name at the end of the sentence, the slight tone of exhaustion, the fact that she said “when are you” and not something like “when will you be able to,” implying that this whole trip was an arbitrary joy ride instead of an effort with actual tasks to be completed. This was all done so discreetly that they both knew it was intentional and yet neither would say it out loud. There is almost nothing so ingenious as the human mind’s ability to sin and then avoid responsibility for it.

“When I’m done,” he said, giving her nothing more. And assuming the worst, Jesse’s heart made a serious mistake. The truth is that Janie was worried about Jesse, was grieving for a father-in-law she loved, and wanted him to find something out about Bruce and where he’d come from. But she was tired, and she knew her husband didn’t love her anymore, and despite the fact that she was trying to make Jesse feel a little of the frustration she was feeling, she was in survival mode, not willfully shutting herself off to Jesse’s pain like he presumed. And she was about to tell him she hoped he was able to find out something about his father when he said, “I was just making sure Jeremiah was okay, thanks,” and abruptly hung up.

His hand was tingling. He smiled, and wasn’t sensible enough to be ashamed of it. Wounded as he was, scared as he was, he was smugly satisfied at being able to throw a punch back and then feel some self-righteous self-pity.

So my wife doesn’t care that my father just died and I’m trying to put together who he was. And I’m losing my job. And instead of grieving like a normal person I’m on the other side of the state springing for a hotel room for a guy I just met. Well. Not many people know what this is like.

But being the main character in that melodrama was only satisfying for a minute or two, and by the time he got to the room he felt hollow and had just the lightest sense of regret. He felt his cell phone buzz, and willed himself not to look at what was almost certainly a confused or angry (or both) text message from Janie. Instead, he gently put the suitcase against the wall next to one of the two beds in the room, laid down on the bed itself, and decided to close his eyes for a few minutes.

“Oh my gosh, Brandon, I’m so sorry.”

“Yeah. Thanks. We’ll head home Monday, probably. She’s sleeping now, finally, but I don’t know how long she’ll stay out.”

“How are you doing?”

“Not well, man. I’m worried about her, and we’re both just brokenhearted. We wanted this little guy so much.”

“I know, man, I know. What can I do? How can I help?”

“Right now, just pray for her. I’m so worried about her. I’ve never seen her like this, Randy. She’s so pale and won’t eat and has said some things I’ve never heard from her, and she’s been either crying or looking numb the whole day.”

“How is she physically?”

“They induced birth, so her body is slowly getting back to normal. But that was really hard on her spirit.”

Randy’s throat tightened. His face felt hot.

“We got to hold him. He was so small, man, and we’re just- Her body is doing well, but she’s devastated, man.”

Randy tried to say something. Nothing came.

“Anyway, I should get back to her, but thanks for calling me back. I love you, and I’ll see you probably Tuesday or Wednesday.”

He cleared his throat. “Yeah. I love you, too.” He hung up. He looked down at the dark gray pavement under the overhang where he was standing outside. The rain was still falling.

They held him. Brandon and Rachel held their baby. Their dead baby.

Randy had a baby. Margaret had a baby.

His chest hurt a little, now, and he turned to go inside. The lobby looked blurry as he stepped inside. What was he doing? Going to the room? No, they were going to get coffee down here in the lobby. So he walked over to one of the couches in the carpeted area past the front desk and sat down.

His stomach turned, and chills ran up and down his back. Three years ago? So the baby would be walking now, right?

He pulled his cell phone back out.

He dialed Margaret’s number by heart.