XXVI – When Randy Smiled (Which Is About Right)

There wasn’t any attendant or employee at the Mt. Airy Forest parking lot Melanie had parked in, and Randy couldn’t find her cell phone to call for an ambulance. So in one of the most unsettling experiences of his five-decade life he put the unconscious girl in the passenger’s seat of his truck and buckled her in, crying and still praying the “Help her breathe” part constantly. There’s a kind of man who prays about God, and while Randy had been such a man for the better part of a life stretching back to long before this girl was born, he wasn’t now. As he put the truck in reverse and looked behind him and blinked the freshest tears away, he was praying with all the muscle and sweat and expectation of a man who had good practice pleading with his Father. He knew the Maker was listening, could hear every heartbeat he couldn’t and had a right to every breath those lungs in Melanie’s chest were or weren’t taking. So “Help her breathe” was the song he was singing, and it was on repeat.

Speed bump number one. Two more and then he could fly. Turn left onto Harrison and he could be to St. Andrew’s in fifteen minutes. No cell phone. It was him and her and this Ford pickup truck, and he had to focus on that. Let the noise in your mind fall away. Speed bump number two. Her chest doesn’t look like it’s rising, but she didn’t feel cold. Please, God. Please, her father is a good man. She was doing a good thing. She’s my sister in this family you make. Please, Father, I’ll do something, I’ll do anything. I don’t want this to happen. Not to her. She’s just a little girl. Please, Father. She’s so young. I’m begging you, Father, please let her breathe.

Speed bump number three.

Let’s get going.

It was a white church. It would have been quaint sixty years ago. Now it was a nightmare. There was something wrong here. Jesse had never had a feeling like this before. His chest was in pain, both his hands were tingling, and he had to fight every impulse to run. But fight he did, and he stepped out of the old trees and into the chest-high grass and weeds that surrounded the place where Dwight told him the worst of it was hidden. There were two vines clawing their way up the side of the church that faced him, meeting about three feet below the roof. They looked like snakes in this light, and that seemed about right.

The church had three windows on that side. All three were broken, but they were too high up and the light was already fading too much for him to make out anything more than shadows inside the place. So he made his way around to what would have been the front door a lifetime ago. It was at the top of four wooden steps that seemed much too wide to him. The paint had mostly peeled off of it now, and so the wood was dark gray. He swallowed as he stood on the bottom of the step. Once he looked inside this place he’d have to decide what to do. Call the police? Despite what the uncle he’d never known he had until today said about dying in peace? Or walk away and pretend as best he could that his father and his grandfather weren’t some kind of murderers? For some reason Janie’s face came into his mind, and he was surprised he didn’t want to push it away. He was less surprised that he did.

Then the stair he was standing on broke, and he cried out. The wood was rotted from seventy or eighty springs filled with Midwestern rainstorms. He looked down at the shards of soft wood under his feet and saw a huge black beetle of some kind dart off into the shadows under the next step. And then he heard the grass and the weeds rustle way out on the other side of the clearing, the side where he’d entered from the woods. He squinted and looked through the weak sunlight, but he couldn’t see anything through the tall grass and the shadows. It could have been a deer.

But Jesse’s fear of being shot by a crazy rampaging hillbilly or a misfiring hunter had fallen away at this point. The only thing he was scared of was finding out. And he decided not to care about that and jumped up to the top step and opened the door immediately.

He stepped in and was immediately disgusted. The place smelled like dead animals and mildew. As fast as his heart was pounding he still had the presence of mind to look at every one of the walls inside the sanctuary, where he was already standing since he now realized this was a one-room church. He couldn’t stop the feeling that he was drowning, but he could make himself look and see that there wasn’t anything obvious in any of the open spots that would have caused the smell. But there were about twenty total pews in two rows that stretched up to the old wooden pulpit whose wood was still in pretty good shape. He walked up the center aisle and looked in the pew to his left and threw up.

He felt just a little better after he realized it was the body of a deer, but he still wished he hadn’t seen it. He didn’t know much about dead animals but he knew it couldn’t have been dead more than a week or two. He didn’t want to think about the way the body looked again, but it wasn’t a relic of his father’s days. That much he knew. He didn’t find anything else in any of the other pews. But when he got to the pulpit and turned around he saw Dwight standing in the doorway he’d come in. And for two seconds he was relieved, thinking his uncle had decided to join him and tell him what this place really was.

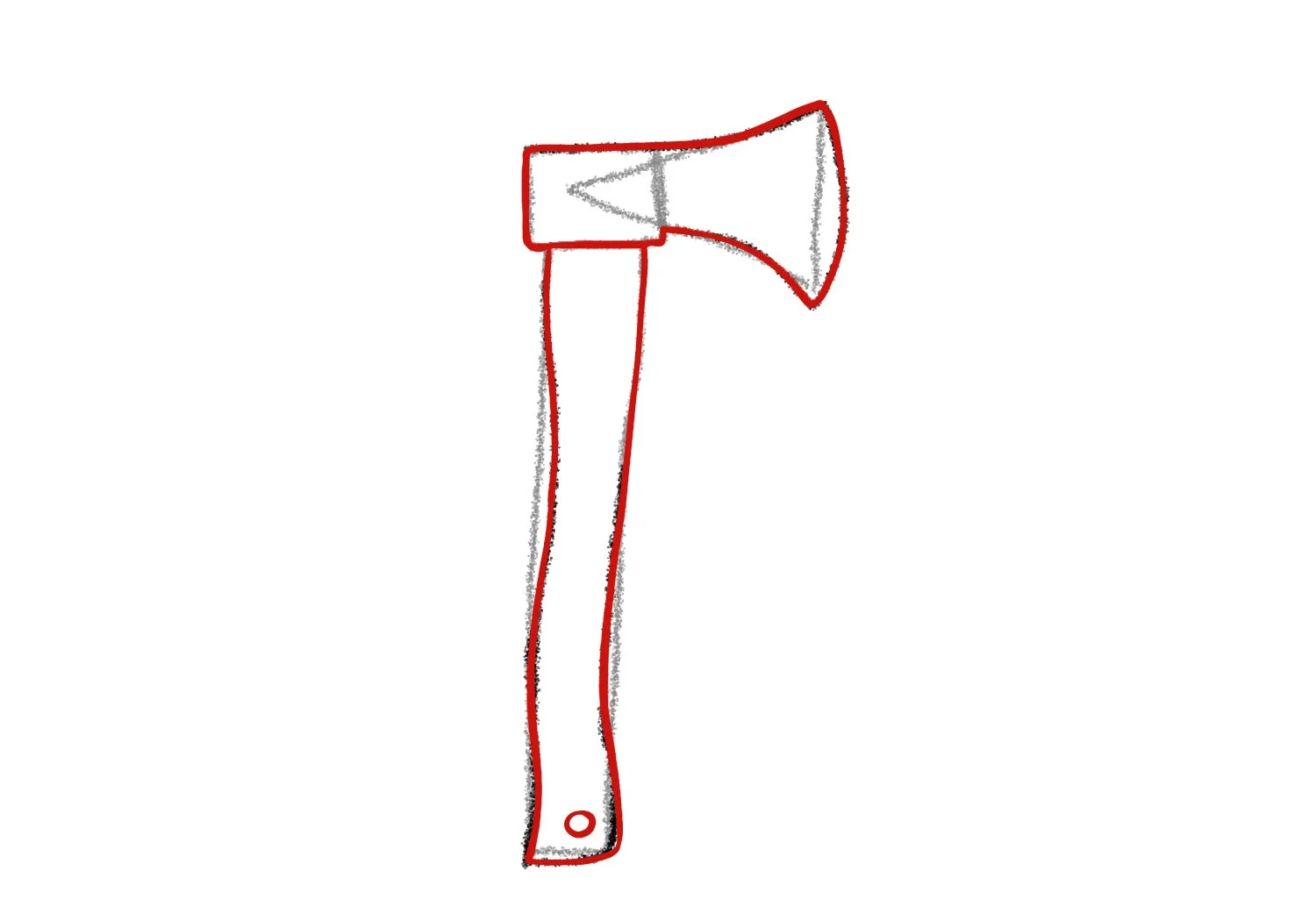

But then he saw what was in his right hand.

And he realized for the first time that his uncle was a big man. Of course he was. He was Bruce’s twin. And he was standing up straight now, like he had been for the first minute or two on his front porch when Jesse had first gotten here. His chest was broad for a man his age. He cracked his neck by stretching it down to his right shoulder. Then he lifted up the ax and put the flat side of its head in his left hand.

“You know what retarded, is, son?”

Jesse just stared at Dwight’s eyes. He was ready for this. How was that? He had no idea, but he was. And so his face didn’t register any surprise, any fear, and that made Dwight stop for a few seconds.

Then he screamed.

“I asked you a question!”

Jesse didn’t flinch.

“Boy, I like you,” Dwight said, and he smiled a smile that made Jesse’s stomach feel sour, almost as much as the bloated deer carcass had. Dwight’s smile showed his top left teeth, and his eyes looked yellow as he gave it, and he took three steps closer to Jesse knowing everything he would say and everything he would do and how much sick pleasure it would bring him. After all, he was dying anyway. That part was true. And Hell was as sure for him as sunrise. So why not take a bite?

“Yeah, you remind me of someone, boy.” His face fell into the shadow of one of the trees on the other side of the clearing as he took the the third step and stopped. “Huck. Your daddy, boy. Our father was retarded. He was a useless sack of muscles and guts that should have been a man. Couldn’t hardly talk. Couldn’t wash his own clothes. Had the smell and the look of a stupid old hound, and that’s why our mamma’ left. But we was boys, and boys can’t leave nowhere. So I kept our retarded old man alive and done what I done to him and Huck. I’m evil, son. There ain’t no other way to say it but what it is. I love pain. I always have. I love seeing their eyes get wide and wondering what’s next, what you’re gonna’ do to their back or their face or all of ’em. Huck wasn’t no better, he was just different. He didn’t like cutting up the animals while they was alive like I did, and he didn’t want the special things I told him we had to do. The things I did to him down under the house in our crawlspace where I loved it. But you should know he wasn’t no better. Maybe you are, son, but things have a way of coming up again and again, so I expect you’re not.

“Huck finally run away and left me with him. I thought about murdering our old man every day. I even thought about eating him. I wanted to hear him scream, hear him hurt in every place. But I didn’t do anything more than burn him with matches and cut him some on his legs. I carved his name there.” Dwight pointed at his own left shin and then laughed, a belly laugh that made Jesse want to kill him. “He was such a crier. But he died twelve years ago. And I hoped old Huck would hear about it and come home to me then. I don’t suppose he did?” Dwight looked up at Jesse with an actual hurt hope in his face that made Jesse feel something like pity. But he didn’t answer. He didn’t move.

“Boy, you just don’t know. I’d have killed them both. Should have. And I’m going to split your throat open with this here ax and drink your blood. That’s what I do. It’s what I am. Never got to kill a real man before, but it looks like I have my chance.”

He took four more steps up to Jesse, smiling the whole time.

They got Melanie into the ER quickly. Randy was able to tell them as much as that she had asthma, he knew she used an inhaler, and that he needed to call her mother and father. While they took her on a stretcher into a room down the long hallway just inside the ER entrance he’d come in, he dialed Pastor David’s number, and he felt the tears stop for the first time.

“Pastor, Melanie was at the park where she was going to meet that friend. I found her on the ground. It didn’t seem like she was breathing. She was unconscious.”

“What! I don’t understand. Where are you now?”

“We’re at St. Andrew’s. The ER. I’m calling you from the front desk just inside the ER entrance. My cell phone died before I even got there.

“What did they say? Is she breathing now? Who can I talk to? Who’s there?”

“No one’s here now, but they just wheeled her into a room down the hall. I can’t tell if she’s breathing or not, and no one said anything.”

“I’m coming. I’m coming. I’ll be there.”

Pastor David was gone. Randy turned around and saw a nurse.

“Is Melanie going to be all right? The young girl I just brought in? What’s wrong with her?”

The woman, a young black woman with pulled back hair and a very calming pitch to her voice said, “They’re going to treat the inflammation and see if her breathing improves. That will take at least a few minutes. Can you answer some questions about her medical history?”

“No,” Randy said, feeling electricity in his left arm. “But her dad will be here in just a few minutes.”

Randy did explain to her exactly what happened, and the nurse nodded sympathetically and didn’t write any of it down, which comforted him because it was a more specifically human reaction than he expected in a hosptial these days.

When he was done talking with her he turned around and thought for the first time that he had just been here, in this same hospital, less than a week ago with Jesse and his father. He had only been to St. Andrew’s twice before last week, and now he’d been here two times in a handful of days. The Emergency Room entrance wasn’t as nice as the main lobby entrance he’d come in with Jesse, though. Lower ceilings and floors that were more worn and scuffed up and almost no windows.

She’s so young. Please, God.

Pastor David came in the sliding doors of the entrance, and he looked like Randy had never seen him before. His face was pale, his eyes were wide, and his tall, skinny frame was jerky and moving like a downed electrical wire.

“Where is she!” he said loudly to Randy as soon as he saw him.

“Back that way,” Randy said, pointing down the hallway where they’d taken her. And he didn’t have a chance to say anything else because Pastor David was gone, a bullet down the hall and finding out from some nurse or staff person Randy saw him talking with which room was Melanie’s. About a minute later he saw Pastor David’s wife come through the sliding doors, her cheeks flush and wet and her eyes swollen. She was holding the right hand of their youngest and the other four were standing on either side, looking not much less frantic than her. Randy told her the direction of where they’d taken Melanie and offered to keep the kids, but she said she wanted to bring them, and Randy could tell from her voice that she was more right than he could hope to be. They were gone down the hall and found the room, and he sat down in a chair that had a torn spot in its faux leather seat and a pair of tiny wooden armrests and put his head in his hands.

He hadn’t prayed this hard since his sister’s cancer scare. Could you die of an asthma attack? Could it happen on the day you tried to save your friend from spiritual suicide? He was neither doctor nor prophet, so his head in his hands and his heart in his mouth was the best he could do. “Please let her breathe, Father. I know I killed my baby. I did it.” And his face was hot now, wet and shaking along with the rest of his head and hot with blood and shame and something else he never knew was coming, not even to the end, but he prayed through it all because Randy was the best kind of man: Desperate and blessed. Would that we were all Randys, love and speeding pickup trucks and big prayers. But this day in this hospital only needed one. Sometimes one is enough.

He was wiping his nose on his shirt when Pastor David’s wife came out with the two youngest and bent down and hugged him and told him that Melanie was going to be okay. And then he lost it, and his face took that shape only the best men’s can take, uncontrollable tears and a smile underneath them. And Pastor David’s wife was sure in that moment she had never met another Christian like Randy, who she’d known less than three years and who four years ago was a pot-smoking abusive husband. There is no God like this one.

She gripped his shoulder and leaned over and kissed the top of his head and walked back to the room where Melanie was already awake, though still breathing in fits. And as she did Randy wondered what he ever did to deserve a life this good. He closed left hand tight, trying to make that electric feeling stop, and he smiled wide, and he laughed. The fake leather squeaked as he slid back and put his sunglasses back on. “You are too good,” he told his Father. And he was right.

It was Pastor David’s wife who found him, twenty minutes later in that chair with his head back against the wall, black sunglasses pointed up towards the ceiling. She didn’t get to see that last smile. But she wouldn’t have been surprised.

She knew the same Father.

Jesse didn’t care if he died. This was probably the first time in his life that was true. Something had happened in his chest and head since the St. Marys Waffle House that made all the difference, and now he was ready to be murdered by an uncle who had made a life of sexually and physically abusing his own father and Jesse’s. And so he stood as still as the maple tree in their neighbor’s yard, the one Jeremiah had kissed because he said that was the special tree, the one that made him think of all of the good things in the world. That was a good tree, and this was an evil place, and somehow those two things made sense now.

Dwight’s face came out of the shadow on that fourth step towards Jesse and now Jesse saw that as big as he was he was also really dying. And so when he tripped and landed on one knee he wasn’t as surprised as he might have been. This was how it ended. This was how it had to end.

Dwight looked at his own left hand, hoping that somehow he could still swing the axe. It wasn’t the same axe he’d had back then, but that was okay. This one would still work. Jesse wasn’t Huck, either, so maybe it was even right. But he couldn’t get the thing out of his left hand. He was stuck, and that pain down deep in his gut was sharper than yesterday. He hated this boy so much, and he loved him so much, and he wasn’t even sure any more which of those was true. He just wanted to make him scream the way he had Huck. Why did Huck leave? He was his. He should never have left. That wasn’t his right. Never his right.

Jesse stepped up to him, the man who looked just like Bruce but the scar and the hair, and he reached his hands down and took the ax from his big hands. Every last whisper of the old fear had slipped under the doors of the church, gone for now in any way that mattered. And he looked down into the eyes of the man who made his father a more broken man than he might’ve been.

“You gonna’ kill me son?”

Jesse thought about it. He knew what Dwight was, knew what he could tell police about the past, regardless of whether Dwight had ever actually murdered anybody. He knew he could say he’d fought for his life. But the thing that had happened was too real for him to be the same man.

“My father died a better way.”

He lowered the ax to his own right side.

“I wish you nothing but the same.”

He walked to the door of the church, never looking back. Dwight could make it back to the farmhouse. But he needed to get that rental car back to Cincinnati. There was something he needed to do.

He was fifteen yards into the woods when he chucked the ax into the green.